Reviews of Lucy’s books

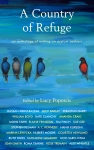

A Country of Refuge (Unbound Books)

A Country of Refuge (Unbound Books)

‘A powerful, and frequently harrowing, collection … I read it with fascination’ Penelope Lively

‘A beautiful insight into the painful individuality of the refugee’ Jon Snow

‘Full of powerful writing. Many of the best contributions come from writers who are refugees, or second-generation refugees, themselves … Again and again, these writers argue for empathy.‘ Samantha Ellis, TLS

‘A first-class collection of essays and poems, stories and memoirs. Addictively readable, they are strong, angry, compassionate and enlightening.‘ Sue Gaisford, The Tablet

from the TLS http://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/public/as-if-there-never-had-been-stories/

Lucy Popescu’s A Country of Refuge is a collection of both fiction and non-fiction about refugees. A moving essay by Joan Smith about Anne Frank’s father’s attempts to seek asylum, comparing it to the story of Aylan (Alan) Kurdi, a victim of “the same depressingly bureaucratic response to refugees fleeing fascist regimes”, proves that empathy is not the preserve of fiction. Not every contribution earns its place. An excerpt from Rose Tremain’s story “The Beauty of the Dawn Shift” is not nearly as powerful as the whole original. It is also a little unclear why two pieces (neither new) by William Boyd about Ken Saro-Wiwa have been included, since Saro-Wiwa was never a refugee. But this book is full of powerful writing. Many of the best contributions come from writers who are refugees, or second-generation refugees, themselves. Hassan Abdulrazzak describes an encounter with an RSPCA inspector who refuses to allow his Iraqi family a dog, and his realization that “it was going to be a long, hard struggle to learn all the rules of my new homeland”; Katharine Quarmby tenderly describes her mother’s induction into the mysteries of The Archers.

Amanda Craig’s fine satire “Metamorphosis 2” riffs on Kafka to imagine a celebrity called Katie F waking up to find she has turned into a “giant cockroach” who hisses her vile xenophobia while safe within her massive carapace, comforted by the fact that “it wasn’t as if she were fat, or tattooed or a foreigner”. Sebastian Barry’s “Fragment of a Journal, Author Unknown” follows one of the tens of thousands of people who fled Ireland during the Famine, risking their lives to cross the Atlantic in “coffin ships”. Like today’s refugees, dehumanized as a “swarm” by David Cameron, Barry’s protagonist knows he is not wanted:

Our sin was that we were poor and therefore nothing. Our sin was that we were too many in the eyes of government and that it would be a blessing on the country if we were to perish. In this way we were described as a plague on our country and nothing more than vermin and rats.

Again and again, these writers argue for empathy. A. L. Kennedy imagines two tourists watching refugees inside an enclosure, like animals in a zoo; “we came for a bit of a show and some action”, says one. “And they’re hungry, aren’t they? It’s like they’re starving. All that grabbing.” Courttia Newland imagines what would happen if British citizens had to flee. “I hadn’t expected that many people to be that afraid” says a man who is trying to save his family. It is a striking, devastating piece of writing that never patronizes the reader nor the refugees who have inspired it.

The Tablet

Review by Sue Gaisford

http://www.thetablet.co.uk/books/10/8664/hard-luck-stories

Towards the end of this magnificent anthology comes the piece that made this hardened reviewer weep. Only six pages long, Marina Lewycka’s “A Hard-Luck Story” is written in the voice of Colin, a man who’s not had much luck. He has finally got a job, working at a deportation centre, when a woman insists on his listening to her story.

She is a doctor whose husband, an academic, has been “disappeared”, and she is about to be deported. Her experience is all too familiar. She managed to get to Libya and was put on an overcrowded boat, whose captain abandoned his passengers. Their boat capsized, and her small son was drowned. She saved her daughter, along with the tiny baby belonging to a woman she’d earlier noticed, who had also drowned. Rescued by people she described as Angels, she eventually got to England. Idly, Colin wonders why this had been where she had wanted to go. “I learn England is a good country,” she explains. But, raped and robbed, she had been dumped in a field, and now had nothing at all apart from the two little children.

Throughout her account, Colin adds his own comments: “Well, anybody can say that,” and, “It’s bloody hard work trying to keep you lot under control … don’t expect no sympathy from me.” When the moment arrives for her to be deported, she is injected with a sedative, and slumps to the floor. Colin hands the baby to the little girl. “That’s a nice touch, Colin,” says his supervisor. “It’s better if they go quietly.” “No more trouble from you, lady,” thinks Colin.

Lucy Popescu works closely with refugees, and has heard many such stories. Some of our finest writers have contributed to this book and the result is a first-class collection of essays and poems, stories and memoirs. Addictively readable, they are strong, angry, compassionate and enlightening. Some are surreal: in Amanda Craig’s “Metamorphosis 2”, Katie F is transformed from airhead celebrity into a cockroach and meets a truly sinister fate, while in “Inappropriate Staring”, A. L. Kennedy seems to imagine a conversation among visitors to the monkey house – or are they actually casually watching a crowd of refugees? Elsewhere, Ruth Padel writes factually about Sangatte, Sebastian Barry about the coffin ships taking survivors of the Irish Famine to America, William Boyd about the death of Ken Saro-Wiwa and Nick Barley about his forebears, who found refuge here after the Hungarian uprising.

Though all so different, themes emerge, particularly the suffering of children. Kate Clanchy writes from the viewpoint of a teacher, whose refugee pupil, Shakila, describes running from a suicide bomber in Afghanistan, while Roma Tearne gives a harrowing account of the death of a small boy who did not get away in time. Joan Smith draws a parallel between Otto Frank, the father of Anne and the only one of his family to survive the Holocaust, and a Syrian Kurdish barber named Abdullah Kurdi, also fleeing with his family from a brutal dictatorship, only to see them all die. He is the father of the little boy, Aylan, photographed so pitifully washed up on the shore of Kos. Both men had relatives longing to take them in, and were thwarted, largely, by bureaucratic red tape. Such is still, far too often, the fate of the persecuted. Elaine Feinstein’s grandfather, fleeing from Odessa a century ago, had seen England as “the country of fair play”. If only that were still true.

The Good Tourist reminds us that it’s the responsibility of all travellers to be aware of how our fellow human beings are treated – at home or abroad. And, as Lucy Popescu makes clear, if they’re treated badly we shouldn’t keep quiet about it. Her timely and realistic conclusion is that if you want to see the world as it really is then leave the rose-tinted spectacles at home.

The Good Tourist reminds us that it’s the responsibility of all travellers to be aware of how our fellow human beings are treated – at home or abroad. And, as Lucy Popescu makes clear, if they’re treated badly we shouldn’t keep quiet about it. Her timely and realistic conclusion is that if you want to see the world as it really is then leave the rose-tinted spectacles at home.

MICHAEL PALIN

The Good Tourist is a fascinating, timely and important book, you will never travel in the same way again.

WILLIAM BOYD

http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/tol/arts_and_entertainment/books/article5250961.ece

http://www.independent.co.uk/travel/news-and-advice/tips-and-deals-1002749.html

http://jonathanfryer.wordpress.com/2008/10/10/the-good-tourist/

http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/excessbaggage/index_20081101.shtml

In The Good Tourist: An Ethical Traveller’s Guide, the author Lucy Popescu gives a useful overview of the arguments for and against a travel boycott of Myanmar. She counsels readers to research the country before they go and recommends The River of Lost Footsteps: Histories of Burma by Thant Myint-U for its insight into the country’s past and present. On the subject of giving local people access to the outside world, Popescu advises caution, saying that local people may be “endangered” if they are seen speaking with tourists. It’s a view shared by Responsibletravel.com

The Myanmar Debate: The National http://www.thenational.ae/article/20090131/TRAVEL/794224330/1015

The Good Tourist: an ethical traveller’s guide, by Lucy Popescu

Reviewed by Judith Rodriguez

PEN Melbourne Quarterly March 2012

It is rare for a book in an accepted genre to offer an original take on the genre. Here is a travel book like no other.

For her travel book, Lucy Popescu, a PEN member of the English and Norwegian centres, has researched an unusual, but reasoned set of destinations: Australia, Maldives, South Africa, Iran, Mexico, the USA, Morocco, Russia, China, Uzbekistan, Syria, Myanmar (Burma), Turkey, Egypt, and Cuba: does that list tell you anything? To those of us who write letters in response to Rapid Action requests from Writers in Prison, it certainly does.

The foreword, written by a former PEN International president, playwright Ronald Harwood, describes how as a boy he gazed out from the South African mainland to Robben Island in the Atlantic Ocean—‘a dazzling sight, in my memory like a tray of beaten silver—a sight which invariably raised his spirits. As an adult he lost this elation. He then knew that the heroes of the fight against apartheid were imprisoned at this former leprosarium.

Here in Harwood’s words is the raison d’être of this book: ‘A tourist, possessed of even a modicum of sensitivity, cannot totally divorce the landscape from historical events or present circumstances.’ He surmises that the beauty of the Bavarian mountains round Hitler’s eyrie is poisoned by the knowledge of Hitler’s deeds, and goes on to refer to current governments’ abuses of power. These are often enough ignored by the international tourist who approaches foreign countries to enjoy their scenery, cultures, cuisine, and the friendship of citizens who may or may not speak of political matters and the repression of human rights.

Popescu has done her work thoroughly. Sections on the touristic offerings of the country, its history, and the state of politics and human rights that history has given rise to, are followed by What You Can Do and Recommended Reading. Yes, there’s fine writing here, and yes, it is a study book. Interesting, shocking, motivating.

We must be shamed by the just inclusion of Australia, with sections titled Red Earth,

The Stolen Generations, Terra Nullius, Outsiders Inside, A Fair Go. The situation of indigenous Australians is forcefully put, with references to the Apology of 2008, to the Little Children Are Sacred review, to the expropriation of Indigenous custodians of land and the removal of children from families. As for our dealings with refugees, Popescu, with the cooperation of Rosie Scott of PEN Sydney, follows the case of Australia’s first Writer in Prison, Ivory Coast journalist Cheikh Kone, and describes the conditions experienced by asylum seekers at various detention centres.

The fact that other countries have kept asylum seekers in indefinite stagnation or deported them back to their place of origin does not fault the book for not including them. Popescu points out that she has had to be selective among an unfortunate wealth of material; but also, the circumstances of our desert detention centres, the government’s effort to ‘export’ the whole issue off-shore or to foreign jurisdictions despite our UN-Chartered responsibilities, the inefficiency of Immigration ‘checking’, the demonstrated fatal results of deportations—all these argue the heinousness of our

treatment of the comparatively few refugees appealing for help to Australia.

Is this a negative book? No! Lucy Popescu is positively elated by her reading of the Australian books she recommends to those interested in Australia (and she makes similar forays into the literature of the other countries she treats).

Her sample bag contains Bail’s Eucalyptus, Franklin’s My Brilliant Career, Winton’s Cloudstreet, Sally Morgan’s My Place, Carey’s Oscar and Lucinda and Malouf’s Remembering Babylon—as well as films. I would be satisfied to have overseas friends approach this country guided by Popescu’s enthusiasm for its finest aspects as well as her opening up of the issues we must face, the injustice we must redress.

http://www.melbournepen.com.au/

Another Sky/Writers Under Siege edited by Lucy Popescu and Carole Seymour-Jones

Another Sky/Writers Under Siege edited by Lucy Popescu and Carole Seymour-Jones

PEN acts as the voice and conscience of everyone who cares about literature. In telling their stories, the incredible writers in this collection uncover some of the world as darker corners. This extraordinary book shows us once again why literature matters. Antonia Fraser

I defy readers not to be profoundly moved by this splendid anthology. But I have no doubt they will also be stirred by the extraordinary courage of all these writers to triumph over injustice and cruelty. This book is an inspiration. Ronald Harwood

Engrossing. Reza Baraheni’s piece is simply electric and others, such as Ken Saro-Wiwa’s letters, deeply moving. More than anything the collection stands as a testament of courage and a clarion call to recognize free expression for what it really is — a basic human right.Monica Ali

This anthology is essential reading for anyone who has ever been moved by the written word. The authors of these pieces have one thing in common. They have all been coerced into not writing. This means that not only do they have powerful stories to tell, but that when, thanks very often to the work of organisations like PEN, they are eventually allowed to tell them, the result is spare, powerful writing, which jolts and challenges our prejudices and assumptions. Michael Palin

From Publishers Weekly: To mark 85 years of work assuring that oppressed writers are heard in their home countries and around the world, the literary and human rights organization PEN presents a collection of essays from some 50 writers; their one common trait, as noted by Michael Palin in a blurb, is that “they have all been coerced into not writing.” Designed to demonstrate the major ways in which writers are silenced, shocking and sobering lessons in author suppression are broken up into sections on prison, death and exile, though the distinction seems arbitrary; the central theme of oppression weighs much more heavily on writers’ stories than the specific methods employed. It’s important, both thematically and practically, to note that PEN does not differentiate between the talents and skills of persecuted writers; as such, not every piece succeeds, and the similarity of the subject matter can make them difficult to distinguish. But grace notes abound, such as Zimbabwean poet, novelist and columnist Chenjerai Hove explaining, “every new word and metaphor I create is a little muscle in the act of pushing the dictatorship away.” As an act of commemoration, as well as a sobering reminder of a world in which writers are frequently-and all too easily-silenced, this is an exceptional anthology.

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. –This text refers to the Hardcover edition.

http://www.nyupress.org/books/Writers_Under_Siege-products_id-5212.html

http://www.bookforum.com/inprint/014_03/864

http://reviews.media-culture.org.au/modules.php?name=News&file=article&sid=2399

Leave a comment